Ok, we all agree – businesses and consumers – that for our restaurants and cafes to continue to deliver quality products and stay in business, we need to raise the price of our products, especially coffee, which has been resistant to inflationary pressures for over a decade. So we get the ‘Why’, but what about the “How”?

How do we find the new price?

How do we know our customers won’t revolt and leave us in droves?

How do we manage this change?

For years culinary schools, online courses and the industry through oral tradition and lore, have taught operators and those planning their entrepreneurial dreams to price from the cost base up (cost-based pricing). Something like Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) equals 30%, Labour equals 30%, Overhead costs equals 30% and 10% equals profit. So people either do the quick math of COGS divided by 30% and boom that’s my sale price, or they find a fancy Excel calculator online, which arguably does the same thing, just a little cuter. Now, beyond the change to those percentages over the years, there are two main problems with using that method only.

The first is that it must be based on an assumed volume of products sold for the % to be correct. You make the assumption you are going to sell 250 coffees a day, but only do 100? Well, your labour will be well out of proportion compared to the assumed % for labour.

The second is it doesn’t consider the customer and their perception of ‘Value’ for your product. i.e. what price a customer is willing to spend on your product and why.

So what can we do?

Well one strategy that can be useful for businesses, with a high frequency of customers, repeat sales and a direct feedback loop (face-to-face) is to survey our customers to optimise our pricing strategy.

In 1976 Dutch economist Peter van Westendorp developed a technique called the Van Westendorp Price Sensitivity Meter (PSM) to determine consumer pricing preferences and thresholds.

The PSM is formed through a multi-question survey that indirectly measures customer willingness to pay. Instead of asking for a single price point, the model assesses a range of prices, offering a more comprehensive understanding of customer perceptions.

The model includes four key questions, with the ability for respondents to add qualifying comments per response –

- At what price would it be so low that you start to question this product’s quality?

- At what price do you think this product is starting to be a bargain?

- At what price does this product begin to seem expensive?

- At what price is this product too expensive?

Collect the results and chart their frequency. Don’t worry, you won’t need to do a diploma in statistics, instead either use an email service like Survey Monkey to survey your customers via email or manually collect responses.

- Ask your customer at the register/when waiting for coffee or via a form (online or paper)

- Record the price results per customer in to a spreadsheet in 4 columns

- Too Cheap

- Cheap

- Expensive

- Too Expensive

- Then use some Excel spreadsheet skills via pivot tables or sign up to a free trial of some data analytics software, like displayr.com, and follow this guide for their system to do all the work for you.

Now, what does this mean?

Determining the Acceptable Price Range

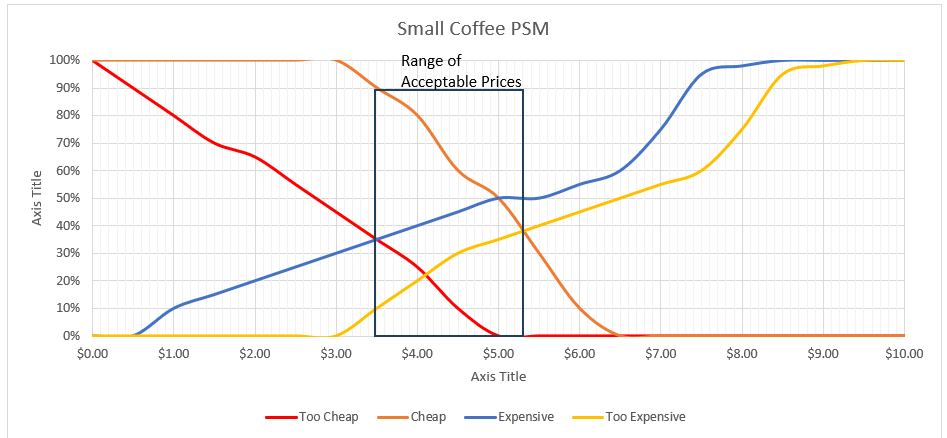

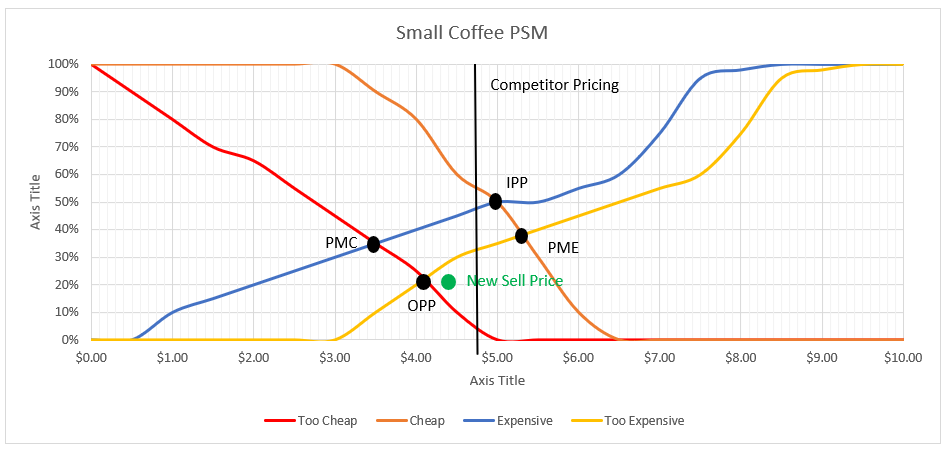

By pinpointing the price perceptions of your customers—whether they view it as expensive, good value, cheap, or too cheap—the Van Westendorp price sensitivity meter helps establish a suitable price range tailored to your target market. It’s common practice to graph all four data points onto a PSM graph, where the x-axis denotes prices, and the y-axis represents the cumulative percentage of respondents for each price point.

By examining the intersections of each series on your PSM Graph, you can determine the Acceptable Price Range for your market and estimate your ideal price.

These 4 intersections are key price points: the point of marginal cheapness, the point of marginal expensiveness, the indifference price point and the optimal price point.

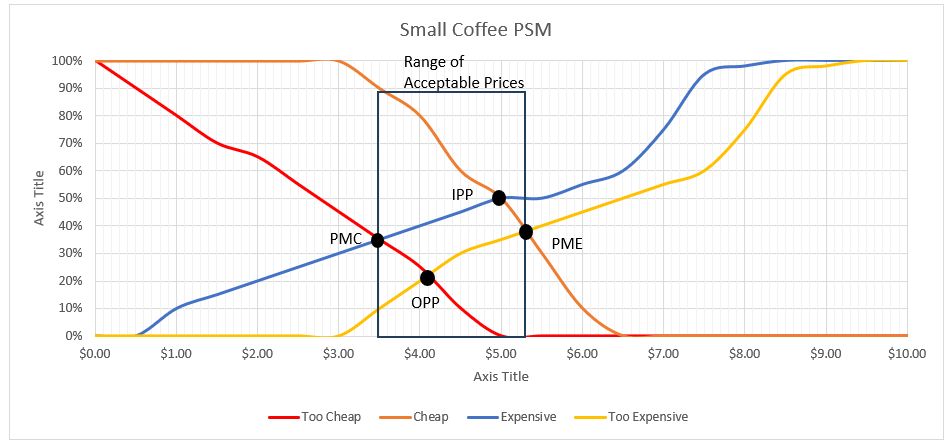

Point of Marginal Cheapness (PMC)

This is the price at which you risk losing most sales because customers perceive the product as low in quality. It’s found where data points for “Too Cheap” intersect with “Expensive”.

Point of Marginal Expensiveness (PME)

This marks the price point where customers lose interest in buying. It’s found where “Cheap” and “Too Expensive” intersect.

Range of Acceptable Pricing

The PMC and PME represent the upper and lower limits of what customers are willing to pay or expect to pay.

Indifference Price Point (IPP)

This is where the percentage of customers who find the price too expensive equals those who consider it cheap. Most customers are indifferent to the price at this point, which is often deemed the normal price for your product.

Optimal Price Point (OPP)

While the IPP is a potential price point, the OPP—where an equal percentage of respondents find the price either too expensive or too cheap—is the sweet spot for maximizing sales and minimizing resistance to price changes. At this intersection, you can achieve maximum sales, making it the best possible price for your product.

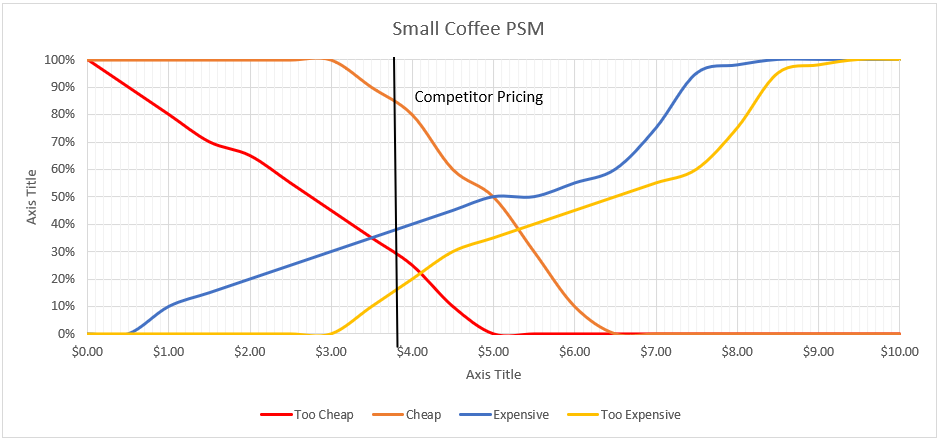

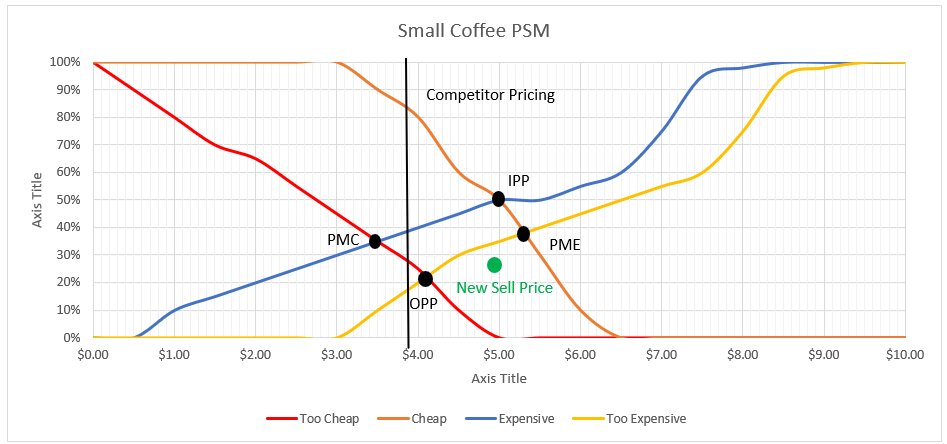

Ok, you now have an idea on your consumer’s behaviour in the event of a price change, but what about your competition?

Well, this is where it can be a little tricky, subjective and beyond the ability of basic statistical analysis to be precise, however, using an element of Value-based pricing is certainly educational.

All you do is add a line for your competitor’s pricing, then add or subtract value based on your value/quality compared to theirs, within your Range of Acceptable Pricing.

Selling high-end, specialty coffee with a variety of brewing methods? Table service? Ok, you might believe your product and service value is intrinsically higher than your competitor serving commodity coffee, takeaway only.

Your value is speed and efficiency, nothing fancy, just quick-fire flat whites to keep your customer fuelled. Ok, so discount your pricing based on the no-frills sales approach compared to the full-service competitor.

Finally, by actively involving your customer base in understanding the necessity and implications of the change, it often leads to a notable decrease in the risk associated when it comes time to make the change in the future.

Limitations & Improvements

Typically, the Van Westendorp model can have some significant limitations, like consumers needing to understand your product and value before doing a survey, doesn’t account for competitors’ actions and doesn’t account for costs (i.e. profitability). But hopefully using common sense, your cost-based pricing as a base; and mapping your competitor’s pricing and your perceived value difference, you can at least have an educated idea about the price, or price increase, your customers and market will accept.

Please note that all graphs and data used to create them are for illustration purposes only. They do not reflect the market, your market, or our opinion on prices. They are simply figures to help illustrate how these types of graphs and analytics work.